RECOVERY – IS THIS AS GOOD AS IT GETS?

Good news keeps coming for Scotland’s economy. This week brought data showing an upturn in the high streets after a dismal spring. Shopper numbers in Scotland were one per cent higher in April compared with a year ago, an improvement from the 3.8 per cent decline in March 2013.

And the latest Bank of Scotland Report on Jobs signalled the strongest increase in permanent appointments for a year during April. Temp billings also grew at a faster rate, reaching a three-month high.

Coupled with growth forecast upgrades from the Bank of England and the OECD last week, stronger mortgage lending numbers and a continuing pick-up in Scotland’s labour market, there is a growing view that we’ve turned a corner.

But a corner to what? To icebergs straight ahead?

A new book by the economist Stephen King, ‘When the Money Runs Out’, should be on everyone’s reading list this summer.

King, who spoke at an Asia Scotland Institute event in Glasgow last week, raises profound questions on our increasing reliance on money printing and ultra-low interest rates to keep the economic show on the road. And it warns that the worst of austerity – or more accurately real austerity - has still to hit home.

It is one thing to move away from the recession precipice and see a pick-up from miserable low levels of activity. Indeed, this improvement is likely to continue.

But the big question now is what will drive our economy forward from here?

There is nothing at all guaranteed about a return to the three per cent plus rates of growth enjoyed before the financial crisis. Indeed, those who predicted a ‘normal’ cyclical recovery and a ‘V’ shaped trajectory for the economy have been proved dramatically wrong.

This not a ‘V’. It’s more like an extended ‘L’ as we bumble along what some describe as “a corrugated bottom”.

Scot-Buzz was been pleased to hail the initial recovery signs from the fourth quarter of last year when the prognosis was uniformly bleak. But equally we have also provided constant reminders of the two great unmentionable words in Scottish politics today – the words that dare not speak their name: deficit and debt.

Very few either side of the independence referendum debate talk about these. And for one reason. They are the single biggest constraint on politicians of whatever hue.

Far tougher action is going to be needed to bear down on a debt total spiralling to £1.6 trillion. And there is previous little evidence that much, if any, progress has been made in rebalancing the economy away from the south-east and away from financial services.

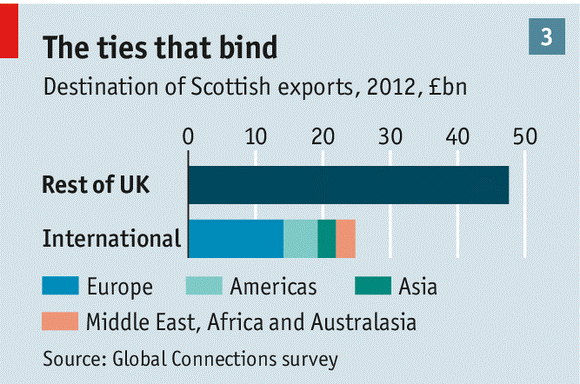

London continues to grow with the dynamics of a global megapolis. But in other nations and regions of the UK – Scotland in particular – there is a major concern over long term growth prospects. Wind farms and North Sea oil provide only partial answers: the economics of the first are highly questionable and the revenue flows from the second subject to huge uncertainties.

The prognosis of Stephen King, chief economist of HSBC, is not at all comforting.

He rejects the label of a doom and gloom merchant. “I would call myself a realist”, he said in an interview with Philip Aldrick of The Sunday Telegraph last weekend, “who doesn’t peddle quick-fix solutions that won’t work.

“The problem with the merchants of stimulus and the merchants of austerity is that the majority have the same underlying belief that the economy is going to rebound rather quickly.

“They just have very different views of how to get there. My concern is that both these sets of beliefs are a bit too optimistic about the nature and speed of the recovery.”

Britain’s big problem, King says, which it shares with the rest of the West, is that it will not be able to grow at a pace that will allow it to afford the commitments made to its people.

“What”, he asks, “if our financial wealth has been accumulated on the back of a delusion?

“What if political promises, even those made in good faith, can no longer be met?”

We are heading, he warns, for an era of weak growth with less prosperity to go round. People will be stripped of their “entitlements”. At the same time growing inequalities of wealth will not only stymy a recovery but lead to intensifying pressure for higher taxes on wealth, one way or another. And he is by no means alone in his view that the long term trend rate of growth has shifted – from around 2.25-2.5 per cent before the financial crash to around 1.25 per cent now.

If true, that is a huge adjustment with which we have barely begun to contend.

I do not believe that we are heading into some permanent cul de sac. Those great mainsprings of human action – adaptation, innovation, enterprise and improvement - are as strong as ever.

But we need to re-create is a climate which encourages these dynamics to thrive and to lift our activity, well-being and prosperity.

And that is not the case now.

In the meantime, the Scot-Buzz web site is throwing open its pages to a free and full debate on the issues raised in this article.

Email your thoughts and reactions – and above all, your suggestions on what exactly we should do when the money runs out.